A few months ago, I tried to code a ZILOG CTC in VHDL. Indeed, I have a long-term project to implement the Drumulator rhythm box from EMU into an FPGA. Why, you might ask? Well, I really appreciate this machine for its simplicity. Plus, I consider it a good project for this kind of development. I've been coding the core of the machine for a few years. That's not really difficult since it just involves using the code of the Z80 processor called T80, which is directly available as open source. A few lines of combinatorial logic in the FPGA, and the Drumulator boots up. At least, its processor part.

The problem with the story is that all the real-time operation of the machine is managed by a Z80 CTC. During my tests, I simulated the operation of this CTC. Simulating means I ensure the CTC behaves the way I know it should respond. The only problem is that this virtual CTC is not programmable, and in fact, I only use the channel managing the display multiplexing. But anyway, the proof of concept was validated.

Indeed, after testing the analog part of this Drumulator, I decided to tackle this CTC anyway. I did find some VHDL 'codes' for a Z80 CTC on Internet, but I was never able to use them correctly for this Drumulator project. The reason is that these codes were designed to react according to the very specific needs of the people who coded them. In fact, they are not complete Z80 CTC codes.

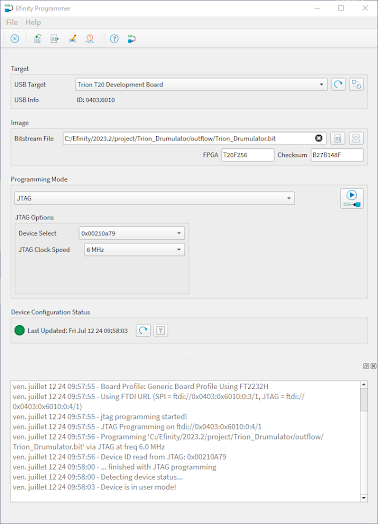

So, a few months ago, I tried again to create this CTC. But in vain. I did manage to get something working with the display board I specifically developed for the Efinix development board, which features a Trion FPGA, but it was impossible to achieve stable operation of the Drumulator's keyboard/display interface. I ended up abandoning the subject because, on top of that, I lacked the proper tools for debugging the VHDL code.

Since then, I have reused the TRION development system for my MSX cartridge. The goal of this new cartridge implementation was to incorporate a processor directly inside the FPGA to handle file transfers from a PC. So, having used the internal processor provided by Efinix to debug the download process step by step, I thought I could use this internal processor to send stimuli to my CTC VHDL code, while also being able to retrieve the state of this CTC, again through the internal processor, and send the result to a text console.

If needed, a few lines of VHDL code 'would be' added to allow the visualization of certain signals directly on the development board's LEDs. This therefore seemed like a very compelling possibility for developing and testing VHDL code. However, as I am not a VHDL coding expert, and having spent a considerable amount of time trying to code the CTC in VHDL, I had realized what could be called a mistake, not in analysis, but in the structure of the VHDL code. This made it harder to understand and very complicated to test without the proper tools. And that's where AI comes in.

I then posed what seemed like relevant questions to an AI and refined the subsequent questions to steer this AI in the direction that suited me best. After a few iterations, I realized that the essence of the CTC was there. Furthermore, the code structure was different from what I had personally developed, but this posed no problem for me in understanding its 'intended' functionality at first glance, and also in immediately identifying potential points of failure, and most importantly, for what reasons.

So, I began systematically testing the VHDL code provided by the AI with the help of the internal processor implemented within the FPGA. And, little by little, I first validated the writing to all the CTC registers, then the various selected modes of the CTC's 4 counting channels, and the reading of the registers. And then, inevitably, the time came to test the interrupt system. This is the stage, I believe, where I failed to validate my personal VHDL code developed a few months earlier. And this interrupt management aspect is crucial for the Drumulator, and obviously for all Z80 systems that use vectored interrupts.

I tested all aspects of vectored interrupt generation: the management of the IRQ pin, the interrupt vector, the daisy-chaining of interrupts, the IEI and IEO signals, and, most importantly, the handling of interrupt ACK from the Z80. It's the same as always—nothing is complicated once you understand how the CTC works, but coding everything correctly in VHDL is not that simple, at least for me.

As a result, I was able to start from the source code provided by the AI, modify it, adapt it, and test its functionality step by step as features were implemented. The outcome is that I managed to test 100% of the CTC's VHDL code functionality. However, I must note that I am not using this CTC with a "real" Z80 but with a Z80 simulated externally via the input/output ports of the embedded processor.

Obviously, I coded the I/O behavior of the embedded processor to react exactly as a real Z80 would. Therefore, I cannot say this CTC is 100% validated as being identical to the original CTC, but from a functional standpoint, it is. And I have a strong presumption that it will work with a VHDL Z80 implemented in this same FPGA. However, one should anticipate that there will be some 'edge effects' during the concrete implementation and use of this CTC.

So, what was the contribution of AI in all this? Well, the generated code served as a framework to follow for developing and testing the VHDL code. Paradoxically, the code produced by the AI seems quite clean and, above all, easy to follow. Obviously, where I thought it wouldn't work, it didn't. But I already knew the reason, so I only had to correct it. In fact, the AI doesn't handle different timing domains at all, but that's not a problem when you know how it's supposed to work.

Finally, I have a functional and tested Z80 CTC VHDL code, ready to be used for real with a Z80 also coded in VHDL inside a TRION FPGA. In terms of time spent, I would say the benefit is total. Of course, I have some knowledge of VHDL, as well as logic, programming, electronics, etc., so I wasn't starting from scratch. But in fact, the time spent on this project corresponded to 30% development and 70% testing, which is a very satisfying ratio for me.

Next step in this subject: attempting to get the Drumulator's processor section running, this time with the help of a "real" Z80 CTC.